Kashmir: Occupied, Partitioned and Disputed

- Aug 1, 2004

- 10 min read

Updated: Mar 15, 2021

While New Delhi’s population tried to escape from a 40ºC heat by slipping into air-conditioned shopping centers some 400 miles to the southeast, we gazed upon a cold drizzle through the open third floor window of a building without energy in the middle of Srinagar, the “summer capital” of Indian-occupied Kashmir. The drizzle slowly turned into snow.

“It last snowed in April in 1987, I guess,” remembers Mohammad Morifat Qadri, publisher of the Afaaq Diary.

Nineteen eighty seven is an emblematic year since it marks the change in posture of some separatist leaders who, because of a great number of arrests and fraudulent elections, decided to take up arms. It was the beginning of a new escalation of military tension in this region, making Kashmir, already hotly disputed by two nuclear potencies – India and Pakistan – for more than 50 years, one of the most militarized territories in the world..

“Maybe it is just a sign of new changes in the situation of Kashmir,” I dared say. “Inshala,” answers Qadri. God willing.

Despite its strategic importance among India, Pakistan, Afghanistan and Tibet, Kashmir has been treated by the global media as a mere point of dispute between India and Pakistan. It is rare to hear about the Kashmiri’s fight for independence and self-determination. Even if newspapers blame attacks on “extremist separatist” groups instead of “terrorists”, readers remain confused about “who wants to be partitioned? and from whom?” There are at least 12 military or political groups acting there, and three major leanings: independence, autonomy, and annexation to Pakistan. There are two agreed points: the retreat of troops and a popular inquiry about the future of Kashmir.

Moreover, there is very little information about international interests in this region, especially in regard to the United States’ global war against terror. Actually, there are as many CIA agents in Kashmir as there are Al Qaeda members, and according to the most recent NATO policies, after September 11, the United States does have a “legal justification” to invade the territory. As a matter of fact, when Pakistan became a major non-NATO ally of the United States the pressure increased on political-military circles to solve, once and for all, the problem of Kashmir. It is not casual that the first formal meeting, since 2001, between Pakistan and India would be happening this month. In 2001 an attack on India’s Parliament, which was blamed on Kashimiri separatists supported by Pakistan, led more than 1,000,000 soldiers to the Line of Control (LoC) - the United Nations-drawn border dividing Kashmir into Pakistani- and Indian-controlled areas. It almost led to nuclear war.

“The international community has been failing to hear the voice of Kashmiri people, maybe because we don’t have oil or anything else to offer,” says Mohammad Yaseen Malik, president of the Jammu & Kashmir Liberation Front (JKLF). One of the first groups to join the fight, JKLF is now devoted to political actions. Malik was one of its leaders in the campaign for boycotting elections in Kashmir. Less than 18 percent of the electors voted and many of them were constrained to go to the polls by military forces. In the day before our interview, Malik had been beaten and arrested during a demonstration in Islamabad, a Kashmiri city. In the following days, he would be arrested again. “After September 11th,” Malik continues, “USA and Europe had to propose new plans for peace and stability to the world, and we hope it also involves Kashmir, through popular participation. We are not able to foresee the future, but sooner or later, we will be unified, with no more LoC, and free from India and Pakistan.”

“I might say with no hesitation that American interests are neither for humanitarian causes nor for justice,” argues Syed Ali Geelani, the president of All Parties Hurriayt Conference, an organization that assembles separatist parties and groups. “Why should we expect any action coming from them or even from international community? Just notice how this global potency has been treating the Iraq prisoners of war! We will continue our efforts at United Nations in order to protect our essential rights, regardless the obvious antipathy Security Committee shows about Muslims. We are all Muslims but, above all, we are humans. We must have faith in the greatest power of all, the power of Allah!”

A History of Occupations

The Vale of Kashmir, famous for its magnificent natural beauty, with vast fertile areas, rivers and lakes surrounded by big high mountains, always arouses dreams of independence in its governors, most of whom have been foreigners. Since the third century A.D., Buddhist, Hindu, Mongolian, Afghan, Muslim and Sikh kings or princes ruled, totally or in part, this Indian state that is currently known as Jammu and Kashmir. Its population always suffered, sometimes more, sometimes less, according to the governor’s personality. The Dogra dynasty, for example, which ruled until 1947, held the “right” to exercise the so called Beggar - to collect people in cities and villages for forced labor, giving them nothing for it, not even food. When they died of hunger, thirst or injuries, they were simply replaced by others.

With the end of British domination in 1947, governors of each state in India had to decide whether their respective territories would be incorporated into India or into Pakistan, based on three factors: territorial contiguity, religious predominance and free will of the people. Despite its long frontier with Pakistan, and the fact that 90 percent of its population was Muslim, the state was ruled by a Hindu Maharaja, Hari Singh. Singh was tempted to grant autonomy to the region but hesitated to make this decision. Only after the eastern part of the territory had been invaded by the Pakistani Pashtun tribes did he decided to sign a statement of adhesion to India. Then the military forces came “to his aid.” Approximately 300,000 Muslims who tried to emigrate to Pakistan are said to have been killed by Dogra and Sikh military troops.

The first war between India and Pakistan for Kashmir control lasted until 1949, when the Line of Control was established, keeping apart many families and fellow-countrymen. Since then, the United Nations Security Council has set many resolutions concerning the Kashmir situation and required the achievement of a plebiscite through which people could decide their own future. However, India has ignored these resolutions and, since 1957, defended its argument that the state of Jammu and Kashmir integrates its territory. From this time on, things have been growing worse and worse. “Typical of any nuclear potency, India is an arrogant and imperialist country, hence it refuses to make international agreements and to accomplish the UN resolutions,” says an international spectator, whom we have talked with.

Conventions and Agreements

In the 1990’s, India allowed the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) to operate in its territory. According to the Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), the Red Cross is allowed to visit prisoners related to the conflict, about 1,500 currently, and to report to Indian authorities how these people have been treated and whether the procedures comply with the humanitarian rules established by the Geneva Convention - the so called International Humanitarian Rights (IHR). The Red Cross, in turn, agreed to keep these reports in confidence and not question the way these arrests have been processed. This is the only possible way to get access to prisons.

“We’ve made some progress and we are extending our actions,” says Robert Przedpelski, chief of the Red Cross’ South Asia delegation. “Since last year, for example, we’ve been providing courses on IHR addressed to the security forces in this region, it might avoid greater problems in the future.” The ICRC has also helped the Red Cross in India to build an orthopedic unit in the city of Jammu, the winter capital of Kashmir, and to improve signaling systems for the big minefields in Pakistan’s frontiers. India did not sign any agreement for clearing the minefields; on the contrary, it has implemented a great number of them during the last decade.

Atrocities

Off the battlefield, the actions of Indian forces, not only in the prisons but also in the streets of Kashmiri cities and in their frequent “Siege and Search” operations within rural areas, are a great terror for all the people. After all, India has approximately 600,000 soldiers stationed in that region, three fold more than the foreign occupation troops in Iraq. These men, whose religion, food, language and culture are different from those of the Kashmiri, are responsible for killing 60,000 to 90,000 persons in the last 15 years - years of terrific atrocities.

The Himalayan Mail, a local newspaper, publishes daily on its first page the “official placard” of persons who were killed in the year. On May 6, the score announced 547 deaths since January 1: 152 civilians, 321 militants and 74 members of security forces. The book “Catch and Kill – A Pattern of Genocide in Kashmir,” published in 1997, depicts details about the 129 extra judicial executions of civilians under custody, including women, elderly and teenagers, that occurred just between Oct. 10,1996 and March 31, 1997. A report in Asia Watch, dated May 1991, documented 100 cases of rape from the village Kuan Poshpora committed by soldiers of the 4th Raj Rifle Regiment of Kupwara, showing 53 testimonies, including one of a pregnant woman, who said that she had been raped in front of her 6-year-old son.

“Indian military occupation of Kashmir has always been illegal, immoral and inhumane,” concludes Syed Ali Geelani. “There are more than 10,000 disappeared persons. People in jails have been tortured with glowing irons and electrical shocks. In many cases, their families receive only pieces of a corpse to be buried. Thousands of villages have been frequently burnt with any sensible reason or justification. Even if there is a mujahedin hidden in one of these locations, there would be no reason to burn an entire village. I could list thousands of dead persons’ names here and none of them was a militant, terrorist or guerrilla fighter.”

Just a few steps away from the main streets of Srinagar we could find in smaller alleys and stores ordinary people who were willing to talk openly about the problems they face. In the district of Dalgate, a man noticed our interest in the children playing around the graves of a cemetery. He came closer to show us the burial places of martyrs that were killed by Indian soldiers - the case of his son. “This is a small cemetery, there are hundreds of larger ones, especially in the mountain villages,” he says. “This will only have an end when Indian forces leave Kashmir and we become finally independent.”

Checkpoints

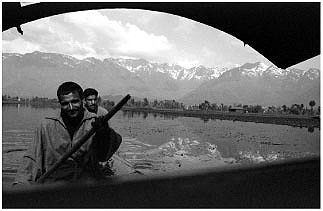

Abdul Geni Wani, whose family lives in Bandipoyra, works at three houseboats (floating hotel rooms on Dal Lake) during the summer. Three of his militant cousins were killed by the Indian army. Despite his position for independence, he doesn’t believe in weapons. “Koran says: a good Muslim should not kill,” he ponders. Wani explains that this is his last working year in Srinagar because he is afraid to leave his family alone. “My oldest son is 15-years-old, the soldiers might come upon him and decide to arrest or kill him, just because they think he is a mujahedin,” he says. He tell us about an episode in which his son witnessed an execution in the middle of the street, and another one in which his son was detained by troops, rifles pointed at his head. I asked him if we could visit his home and he answered that we would need to provide an authorization card showing his village address in order to cross the checkpoints.

But there is no need to take secondary pathways to be stopped at Kashmiri checkpoints. They are everywhere. To visit the small Hindu temple of Shankaracharya, we have to travel a 4 k.m. road with three checkpoints. Personal inspections and metal detectors are also common in bank entrances, post offices and mosques. In the main mosque, the great Hazart Bal, the cleric Bashir Aamad Farroqi addressed a sermon on May 3 to 15,000 persons, among soldiers and rifles.

Along the road to Gulmarg, a ski resort one hour from downtown Srinagar, there are soldiers every 100 meters. Around Dal Lake there are soldiers every 10-15 meters. Boatmen who drive the shikara (a typical boat similar to a gondola) must stop at the post located in the middle of the lake to show their work authorization and identify all their passengers. It’s no surprise that the presence of tourists is quite rare.

Mental Health

Constant tensions, military occupation and the abusive actions of soldiers have also made a great impact on the population’s mental health. There is no more night life and options for amusement grow scarce. Only one of the 12 movie theaters operating in Srinagar in the early 1990’s remains open; likewise, there are only two functioning bars among the hundred’s that existed before. “Due to the conflict, there are great needs in mental health sector of the population,” says Stuart Zimble, chief of Doctors Without Borders’ (DWB) Delhi delegation. “We helped to restore the infrastructure of the unique psychiatric hospital in the state, and we also requested one part of the building with an external entrance to provide advising services to people who have been affected by continuous stress or post-traumatic stress.”

Saskia Ohlin, DWB’s delegate in Srinagar, tells us that cases of people who lost their relatives in the conflict, or were arrested and tortured, or witnessed attacks, are quite common. “But most of the persons that come to us are affected by problems related to prolonged stress, such as depression, headaches, apathy, palpitation, insomnia,” she says. Up to 200 patients visit the medical office daily. The institution has been trying to reach zones hard to access, especially those near the Line of Control. DWB has a weekly radio program, in which some dramatizations concerning ordinary situations are presented. “Our advisers are the local workers we train and supervise, and they advise people to share their troubles with friends, to attend parties, to listen music, to pray.”

Solution?

As I was about to end this article, I read in the newspapers about a new attack by Hizbul Mujahideen, a Pakistan-based rebel group. More than 33 people died, among them the wives and relatives of Indian soldiers. The Associated Press published a statement from the new Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh: “The persistence of this senseless violence in Kashmir is yet another indication that terrorism continues to pose a grave threat to our nation’s integrity and progress, while we will continue to seek peaceful resolutions.” At this same time, I thought of a report that had been restricted to Kashmiri newspapers, only. Two weeks before, the operation commander of Hizbul Mujahideen, Ghazi Shaha-ud-Din, had been led to the interior of a house in Gurgadi Mohalla by the police before the view of tens of people. He later turned up dead. The official version says, obviously, that a gun fight took place after police discovered his hideout. The news goes on being manipulated.

I decided to send an e-mail to a Kashmiri colleague to get his opinion about the new Indian government and to find out if the perspectives related to the meeting between India and Pakistan had been changed. Mohammad Qadri answered that he is still optimistic, that members of the new office are all old leaders of the Congress Party and, therefore, they know more than anyone the question of Kashmir because they also participated in the agreements between Pakistani and Kashmiri leaders in 1971 and 1975. He adds also one more important notice: soon after the meeting, the Indian Union Home Minister, Shiv Raj Patil, will finally meet the leaders of the All Parties Hurriayt Conference. This might be indeed the beginning of a solution for the question of Kashmir. Inshala!

Link original da matéria

Comments